I remember her dress.

It caught the wind,just a little. Enough to move. Enough to flutter like something alive. Not frantic. Not pleading. But deliberate, somehow. Like a signal you didn’t know how to read.

People talk about remembering the important things,the order, the muzzle flash, the arc of the commander's arm. They talk about the facts like they matter.

But I remember her dress.

And how it moved.

I was twenty.

A college kid from Akron. I spent my summers working the meat counter at a grocery store with sticky floors and soft cheese that stank even before its date turned. I wore the uniform because it paid. Because I didn’t want to lose my draft deferment. Because my father said it would make a man out of me.

He was a tool-and-die guy, proud of it, voted for Wallace in ’68 and called the war "a mess, but our mess." He thought the kids on campuses were spoiled. Thought we should crack down. He said "freedom’s got rules, son," and thought that was the end of the conversation.

I had a girl back home who wanted to get married. She kept talking about wedding colors, and I kept saying things like maybe next summer. I didn’t have the courage to end it and not enough heart to stay. So I wore the helmet. I carried the rifle. I told myself I was doing the right thing because I didn’t know how to do anything else.

I wore the uniform like it might answer something.

But it only asked more.

They flew us into Kent State University because the campus was on fire. Literally. The ROTC building had gone up, black smoke drifting like a bruise across the sky. The students said they didn’t do it. The governor said they did. The papers ran headlines before the ash even cooled.

By the time we got there, there was already tension in the trees. Like the branches were braced for something. Like the campus itself had gone brittle.

We were told to be visible. That word kept coming up. “Presence.” As if our boots on that ground would steady something, keep the chaos in place.

But it felt off from the start.

I don’t mean just nervous. I mean off. Like a tuning fork vibrating inside your chest. Like you’d been waiting for a voice to call you home and what you got instead was static.

The crowd started small. A few kids with signs. Chanting. Mocking. One held up a drawing of Nixon with a pig nose. Another shouted something about Cambodia.

They didn’t seem dangerous. Just loud.

But noise can become threat. Especially when you’re already afraid.

We were lined up near the blackened timbers of the ROTC building,bayonets fixed, gas masks ready. The air still smelled like scorched books and anger. The kind of smell that settles in your teeth.

We were issued eight rounds apiece. I remember the feel of them in my pocket, heavy, inevitable. The sergeant said we wouldn't need them. Just a precaution.

He said that with the same look my father gave me before I went on a date with a girl he didn’t trust. That look that says you’ll figure it out.

He didn’t mean it as comfort.

We moved like pieces on a game board,up the hill, across the Commons. We kept our formation. Said nothing. Weren’t allowed to. The students called us baby-killers, fascists, robots. One kid threw a can of Pepsi that bounced off a boot and made a hollow sound, like knocking on a coffin.

Someone yelled, "You won’t fire. You don’t have the balls."

And we didn’t. That’s what we believed.

But belief doesn’t matter much when the air gets heavy.

And the air was getting heavy.

We were told to disperse them. Told to keep the line. Told to maintain order. But the orders contradicted each other. You can’t break a crowd and hold a line at the same time. You can’t threaten violence and promise restraint.

And no one told us what to do when they laughed.

Because that’s what they did. They laughed.

Like we were a joke.

Like they knew something we didn’t.

Or like they were waiting for us to prove them wrong.

We split. Some of us moved toward the Victory Bell. I was with the group that veered toward Taylor Hall.

The students followed.

That’s the part I keep circling back to. They followed. Even when we turned. Even when we moved uphill. Even when we passed the boundary where campus bled into open grass. They kept coming.

Throwing rocks. Screaming.

But also laughing.

That laughter had weight to it. Like defiance disguised as joy.

We reached a fence. Couldn't go farther. Had to turn. Formed a half-circle on the hill. Below us, hundreds of students clustered, some sitting, some standing. Some waiting like they didn’t know what for.

I remember looking at a girl in a denim skirt sitting cross-legged on the pavement, as calm as if she were waiting for class to start.

I remember thinking: They don’t believe we’re real.

And maybe we weren’t.

Not until the gas canisters started to fly.

A canister rolled near my boot, leaking smoke. Someone picked it up and threw it back. It hissed across the asphalt and landed among us. No injuries. Just noise.

We were ordered to turn.

And that’s when it happened.

That’s when the air changed.

Not the temperature. The pressure.

Like a door had closed. Somewhere unseen. Somewhere final.

I heard a shot.

Then another.

Then a chorus.

They say it lasted thirteen seconds.

Sixty-seven rounds.

Twenty-eight of us firing.

Some into the air.

Some into the ground.

Some, like me, into the crowd.

She wasn’t running.

She wasn’t holding anything.

She was just there. Standing. Her arms loose at her sides.

Her dress moved in the wind.

And then it stopped.

They tell you firing a weapon is deliberate. Calculated.

They’re wrong.

In that moment, you don’t think I’m going to shoot.

You think: She sees me.

You think: She’s not afraid.

You think: She is everything I gave up.

You think: I have to do something.

And the trigger is already moving.

I didn’t aim for her.

But I didn’t miss.

She staggered.

She folded like laundry dropped to the floor.

Arms wide, knees bent wrong.

Blood poured from her like it had always been there, waiting beneath her neck for permission to spill.

Someone screamed.

Someone else ran toward her.

But no one touched us.

Not then.

They just watched.

We stood there, silent.

Guns still hot.

Smoke curling in the sunlight.

The crowd was gone before we understood what we’d done.

I don’t remember the walk back to the barracks.

I remember taking off my helmet and setting it on the floor like it might explode.

I remember the sound of someone vomiting in the hallway.

I remember my hands shaking so hard I couldn’t get the buttons on my shirt undone.

I remember no one speaking for hours.

And I remember thinking: It can’t be undone.

Not ever.

I didn’t tell anyone which shot was mine. I didn’t need to.

I saw her fall. I felt it like a fracture.

Like something inside me cracked and never healed.

They said four dead.

Nine wounded.

They called it a tragedy.

They said we had no choice.

That we followed orders.

That we were provoked.

That the students were out of control.

That America had to protect itself.

But no one protected her.

No one protected us, either.

I never wore the uniform again.

I got my discharge quietly.

Moved back home.

Took a job at a hardware store where no one asked questions.

Married the girl, though we never talked about it.

She left two years later.

Said I wasn’t in the room even when I was.

She was right.

I never came back from that hill.

There were hearings.

There were photos.

There was that Pulitzer image of the girl screaming beside the body.

There were protests.

There were excuses.

And then there was silence.

We don’t talk about Kent State.

Not really.

We talk around it.

The way you do when you know a thing still has teeth.

Now I see it again.

The old language returning.

“Enemies.” “Order.” “Retribution.”

A president convicted of crimes calling for military action against our own people.

Saying he’ll build camps.

Saying he’ll punish those who disobey.

Calling protesters “vermin.”

He doesn’t use metaphors.

He means it.

And the boys in uniform?

They’ll be twenty.

They’ll be from Akron.

Or Topeka.

Or Sacramento.

They’ll have girlfriends and fathers and jobs waiting back home.

And they’ll be told the same things I was.

“Just be a presence.”

“Hold the line.”

“Do your duty.”

They’ll be given rifles with eight rounds and safeties that mean nothing.

They’ll be promised order.

They’ll be abandoned when the air turns.

It has happened before.

It will happen again.

You will be told it’s for your safety.

You will be told you are protected.

You will be told someone has it under control.

But you will feel it, the tuning fork in your chest.

And you will know.

I didn’t die that day.

But I didn’t walk away whole, either.

And every day since has been a kind of after.

I remember her dress.

And how it moved.

And then how it didn’t.

A Reckoning: From Kent State to Los Angeles

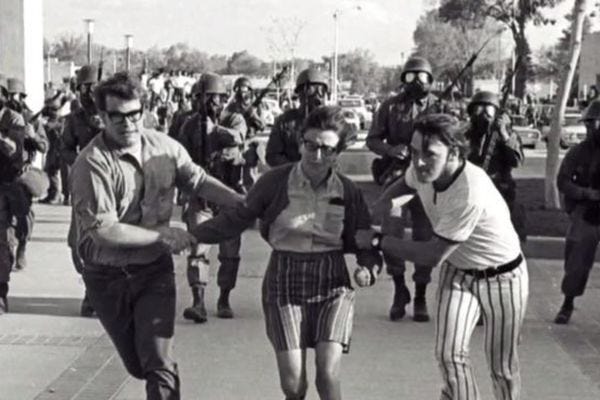

Kent State occupies a peculiar place in the American imagination ,a day when the country’s promise faltered, exposed to the raw edge of its own contradictions. Four students killed, nine wounded. The images of that day remain etched into memory,the girl in the denim skirt, frozen in time, a figure both fragile and resolute. It was a moment when orders given in the name of “order” fractured the fragile social contract, when young soldiers,just barely men,were asked to police their peers with rifles and eight rounds each, promised that they would not need to fire. And yet they did.

The official narrative has long been one of inevitability, “tragedy,” “provocation,” “following orders.” But beneath the bureaucratic language there lies a deeper fracture, one that continues to widen.

Today, in Los Angeles, the echoes of Kent State reverberate once again. The National Guard is deployed to streets where protests swell against an administration that has cast dissent not as democratic expression but as criminal insurrection. The language is harsher now, more direct: protesters labeled “vermin,” talk of camps, secret orders that strip away legal protections, that defy the boundaries of local authority and constitutional law. These are not the cautious euphemisms of the past but open declarations of hostility toward the very citizens these soldiers are sworn to protect.

The young Guardsmen and women called up are not so different from those who marched onto the Ohio campus decades ago. They come from small towns and sprawling cities, from Akron and Topeka and Sacramento. They have lives and families waiting for them, futures that may never fully recover the weight of what they are asked to do. And yet, they are given orders: “hold the line,” “maintain order,” “be a presence.” Promises that safety will be kept, that the violence will be contained. Promises that echo hollow when the air grows thick with tension.

The protesters they face are not disorganized mobs but citizens claiming their rights with quiet defiance ,standing still amid tear gas, facing rubber bullets, holding their ground with the same fragile courage as the girl in the denim skirt. This is not chaos but a reckoning. A nation confronting the erosion of its own democratic soul.

The past is never past. History waits patiently, like a tuning fork inside the chest, vibrating beneath the surface. The pressure builds. The air grows heavy.

We are reminded that the forces of repression do not arrive fully formed but begin with orders whispered into the ears of young soldiers,orders that demand loyalty over conscience, obedience over reflection. And once the trigger is pulled, once the line is crossed, the consequences ripple outward,lives lost, families shattered, trust broken beyond repair.

The administration today openly undermines the foundations of law and democracy. It embraces authoritarian language and tactics, flouting the Constitution while demanding fealty. This is not the stuff of quiet governance but the beginning of a dangerous experiment in state power.

As in 1970, the question remains: who will remember the lessons of Kent State? Who will resist the siren call of violent order? Who will stand with those who refuse to be silenced?

The answer is not assured. The future depends on the choices made in these charged moments, on the willingness of individuals to see beyond orders and slogans, to recognize the fragile humanity beneath the uniforms, and to refuse the repetition of tragedy.

The wounds of Kent State bleed into the present, and the nation’s conscience is tested once again.

If this piece resonated with you,if you felt the weight of memory, the echoes of history, and the inevitability of its return,consider subscribing to my SubStack.

Stories like this take time, thought, and care, and your support helps keep them alive. A paid subscription means more depth, more truth, and more space to explore the past and the present.

Thank you for reading.

I was there that day in 1970, at the bottom of the hill. I am crying as I read this, like it was yesterday.

I remember that day. The shock of it. May, 1970.

You have to be older, like me, to remember the shock and pain, and the aftershocks.

I don’t want another Kent State. Ever.