Triangle

A Ballad

You must imagine the room as it was that morning.

Not the fire. Not the smoke.

Just the room, and the girls inside it, singing.

Because they did sing sometimes, the girls on the ninth floor. In the last hour of Saturday when the light came slanting through the tall windows and the week was almost over. They sang the songs their mothers taught them, the ones that carried over the ocean in their throats, the ones that made the machines sound less like machines and more like accompaniment.

Rosa had a voice like water over stones. Sarah hummed while she worked, a low steady sound that the girls around her would lean into without knowing they were doing it.

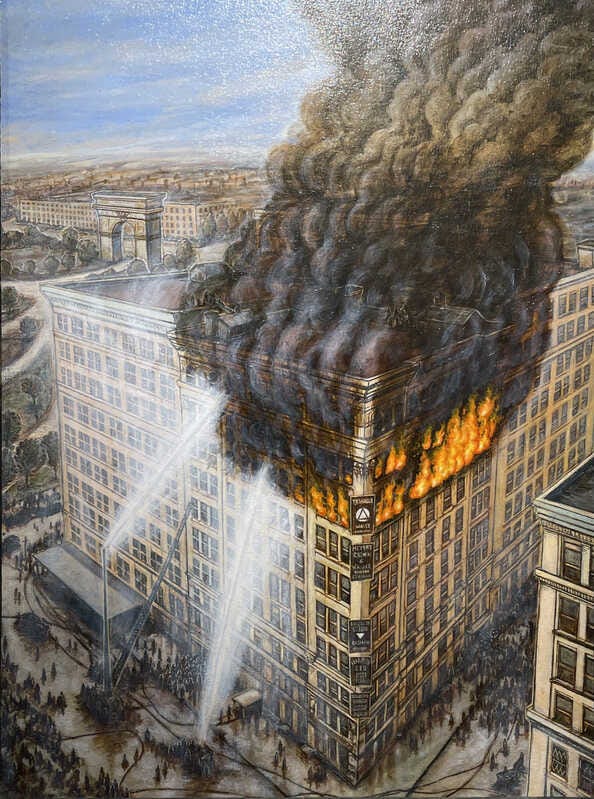

This is how it begins: with voices, with girls, with Saturday afternoon light on the eighth floor, the ninth floor, the tenth floor of the Asch Building at the corner of Greene Street and Washington Place.

March 25, 1911.

Most of them were young. Fourteen, fifteen, sixteen. Young enough to believe that work would save them. Young enough to send money home in envelopes with their mothers’ names written carefully on the outside.

Rosa, sixteen, kept half her week’s wages folded inside an envelope she had not yet sealed. She had written her mother’s name in the old script, the way you do when you need a thing to be recognized across an ocean.

Sarah dreamed of buying a typewriter, because she had learned that sometimes the only way to live in a new country is to write your way into it.

They had come from Sicily and Russia and Poland, from places where girls like them did not have choices. They had arrived in New York believing that in America, even poor girls could choose their futures.

The fire began at 4:40 on a Saturday afternoon.

Nearly closing time.

A scrap bin on the eighth floor caught fire. Someone saw it. Someone said it would go out on its own.

It did not.

The foreman tried the hose. The valve was rusted shut.

There was no water.

By the time anyone understood that this was not a small fire, smoke was already rising through the floorboards to the ninth floor where two hundred and sixty girls were bent over their machines, finishing the last shirtwaists of the day.

The phone rang with a warning from the tenth floor.

No one heard it over the sound of the machines.

When Rosa looked up from her work, she saw smoke curling between the floorboards like something that had been waiting there all along.

She stood. She said fire.

Quietly at first, the way you do when you’re afraid of being wrong.

Then louder.

FIRE.

Everyone ran.

Not panicking. Not yet. Just running toward the exits, toward the elevators, toward the doors that are supposed to open.

The Washington Place door was locked.

The girls pressed against it three deep, four deep, pushing, pulling. The handle wouldn’t turn. Behind them the smoke was getting thicker. Behind them girls were screaming.

The door was locked because the owners had decided that girls might steal. That inventory mattered more than exits.

The man with the key had already gone home.

The handle was too hot to hold.

Some girls ran for the elevators. Joseph Zito and Gaspar Mortillaro, the operators, made trip after trip, rising through smoke, opening the doors to find the ninth floor a wall of girls reaching, pleading.

Zito took twelve girls at a time. Sometimes fifteen if they stood close.

He kept going back. Even when the shaft filled with smoke. Even when the cables began to scald his hands.

On his last trip down, when he opened the doors on the ground floor, three girls fell into his arms.

One was already dead, her eyes still open, still looking at something no one else could see.

Some girls ran for the fire escape.

The fire escape was twenty-four inches wide. Built to satisfy a code, not to save lives. It ended at the second floor in a courtyard with a glass skylight. It had never been tested.

The first girls out must have felt saved.

Air. Light. A way down.

Then more girls came. Ten, twenty, thirty, climbing out the windows, stepping onto the iron platform, believing in metal the way drowning people believe in anything that floats.

The platform held for a moment.

Then the bolts pulled free from the brick.

The fire escape folded, slow and inevitable, and twenty girls rode it down through six stories of air and crashed through the skylight into the basement below.

The sound was like a building exhaling.

Like metal giving up.

Like the moment hope understands it was always a lie.

The rest went to the windows.

Girls standing on the window ledges of the ninth floor, the tenth floor, their hair already burning, smoke pouring out behind them like dark wings.

Girls holding hands.

Girls crossing themselves.

Girls looking down at the street nine stories below where crowds had gathered and firemen were raising ladders that reached only to the sixth floor.

When the first girl jumped, the crowd gasped.

When the second girl jumped, someone screamed.

The firemen spread nets. The nets tore. Or the bodies went through and hit the pavement anyway with sounds the witnesses would hear for the rest of their lives.

Fifty-four girls jumped or fell from the windows that afternoon.

Some jumped alone.

Some jumped in pairs, holding each other.

Some jumped with their pay envelopes still in their hands.

Even falling, they were thinking about the money, about the mothers and fathers who depended on those twelve dollars.

Rosa jumped from the ninth floor with her eyes closed.

Witnesses said she looked peaceful. Like a girl stepping off a train.

She landed on the pavement outside the Washington Place door. The door she had tried to open. The door that was locked to keep her in.

The envelope was still in her pocket, her mother’s name still legible, the money still folded inside.

The fire burned for eighteen minutes.

One hundred and forty-six people died.

One hundred and twenty-three women and girls. Twenty-three men.

Most of them between fourteen and twenty-three years old.

The funeral procession stretched for miles. One hundred thousand people walked behind the hearses in the rain. Another hundred thousand lined the streets to watch.

The owners went to trial. Max Blanck and Isaac Harris, the men who locked the doors.

The jury deliberated for two hours.

Not guilty.

The owners collected insurance money. They opened a new factory. They hired new girls.

But something had shifted.

Frances Perkins stood in Washington Square that day and watched the girls jump. She was having tea nearby when she heard the fire bells. She ran to the scene. She stood on the sidewalk and watched bodies fall and decided in that moment that her life would be dedicated to making sure it never happened again.

She became Secretary of Labor under Franklin Roosevelt. She wrote the New Deal. She built the framework of American labor law on the ashes of the Triangle fire.

In the months after, the Factory Investigating Commission inspected every factory in New York. They found locked doors in hundreds of buildings. They found fire escapes that ended in midair.

They wrote new laws. Fire drills. Sprinkler systems. Unlocked exits. The right to leave a building if you believe you’re in danger.

The International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union grew powerful. Workers struck. Workers demanded. Workers understood that the only way to keep factories from burning them alive was to refuse to enter burning factories.

Laws changed because one hundred forty-six people died and the city couldn’t bear to let their deaths mean nothing.

Sarah survived. She lived sixty more years. She married. She had children who had children.

But she never sang again. Not the way she used to.

Near the end of her life, a reporter asked her what she remembered most about that day.

She was quiet for a long time.

Then she said: “The sound the door made when we pushed against it. Like it was laughing at us.”

Rosa’s mother received the envelope.

She opened it. She counted the money. She understood that her daughter had thought of her even at the end, even in the smoke, even when there was no door that would open.

She kept the envelope for the rest of her life.

When she died, it was buried with her,her daughter’s handwriting pressed against her heart, the last thing Rosa touched, the last proof that she had lived.

The Asch Building still stands at the corner of Greene Street and Washington Place.

It’s called the Brown Building now. Students walk through it every day without knowing what happened there.

But sometimes, on March 25, people gather. They read the names aloud, all one hundred forty-six of them.

Rosa Bellaria.

Sarah Kupferschmidt.

All of them.

So that for one day each year they exist again as something more than numbers. As girls who sang while they worked. As girls who believed in America even as America failed them.

This is the saddest story because it’s true.

This is the saddest story because it keeps happening,different girls, different fires, different locked doors, but the same song underneath.

We tell ourselves stories in order to live.

But this story tells itself.

It rises up every time a door is locked from the outside.

Every time someone decides that profit matters more than the people who generate it.

The girls are still singing.

You can hear them if you listen.

In the hum of a sewing machine.

In the sound of a door unlocking.

In the laws that say you have the right to leave, to be safe, to survive your work.

In every factory that doesn’t burn.

In every worker who goes home.

This is how it ends:

With an envelope.

With a mother’s name written carefully.

With the knowledge that love survives even when everything else burns.

With one hundred forty-six voices singing in a room that no longer exists, in a city that built itself on top of its tragedies and keeps rising, keeps trying, keeps failing, keeps remembering.

The girls are still there.

They are there in the disasters that don’t happen, in the lives that continue because theirs ended.

Because forgetting is its own kind of fire, and memory is the only water we have to fight it.

If this work moved you, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Supporting independent writing helps ensure stories like these,stories that need to be told and remembered,can continue to be researched, written, and shared. Your subscription makes this work possible.

That one line, “Like the moment hope understands it was always a lie,” is such a gut-punch as I can immediately think of multiple instances, especially in American politics for the past decade, where that rings true. Very well-crafted sir; we’re lucky to have such a brilliant raconteur.

Very moving Tom Joad. 🙏

Grateful to the brave and tenacious women that brought about changes for generations that followed.